by Vera Tachtaul

Originally published online with the Richmond Hill Liberal, September 21, 2023

With the start of another school year, it is interesting to look back at our school history, as Richmond Hill celebrates 150 years.

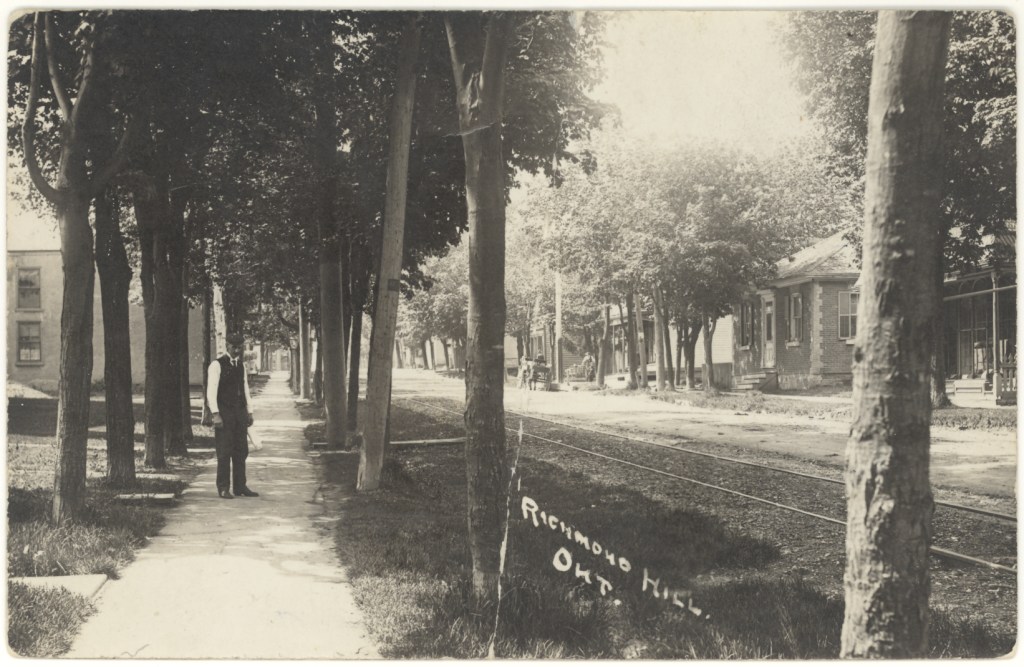

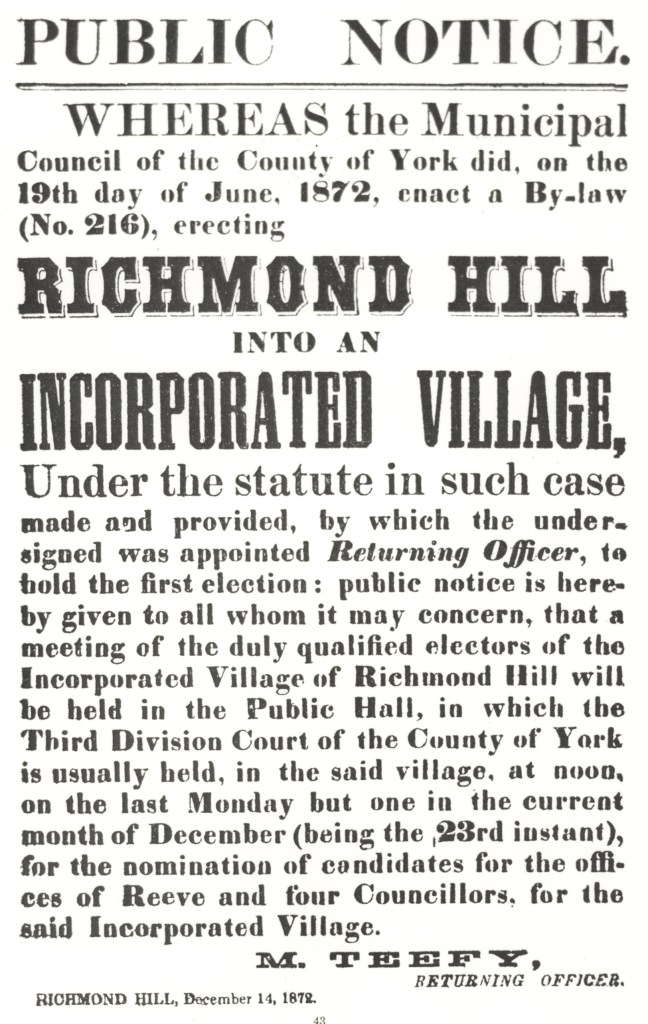

Richmond Hill High School is one of the oldest schools in York Region, and has moved several times in its long history. After Richmond Hill was incorporated in 1873, a school was built behind M.L. McConaghy Seniors’ Centre (as we know it today) that served the community for 23 years until it was destroyed by fire in 1896. The Board of Education set up a makeshift school at Temperance Hall, located at 11 Centre St. W., and rented it for $6 a month. Sixty desks with seats were purchased for $2.95 each from Newmarket Novelty Works.

was marginal compared with today’s standards, and the dilemma of where this new school would be built became the concern. In a letter to the editor of the Liberal, one resident voiced his concerns over the location and the style of this new school, stating that communities were judged by the appearances of the schools that were built there and that the school grounds were just as important for satisfactory educational results.

When the education committee met with the village council to discuss the situation further, three possible locations for the new high school were discussed. One was at the site where the school had burned down, and the other was at Village Park. The third option was at the Richardson estate at the north edge of town, but since no vote was taken, a committee was established to consider the purchase of half an acre of property from the Powell family for $800. Another was to purchase the Hopkins property, which was located at the corner of Yonge and Wright Streets.

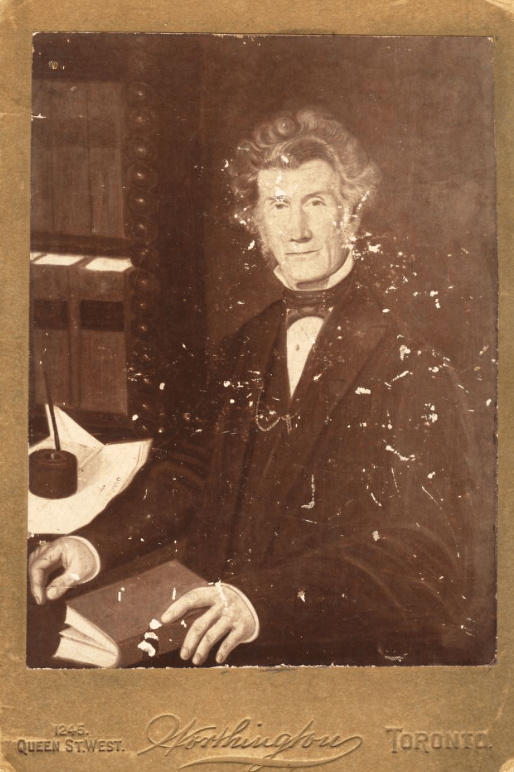

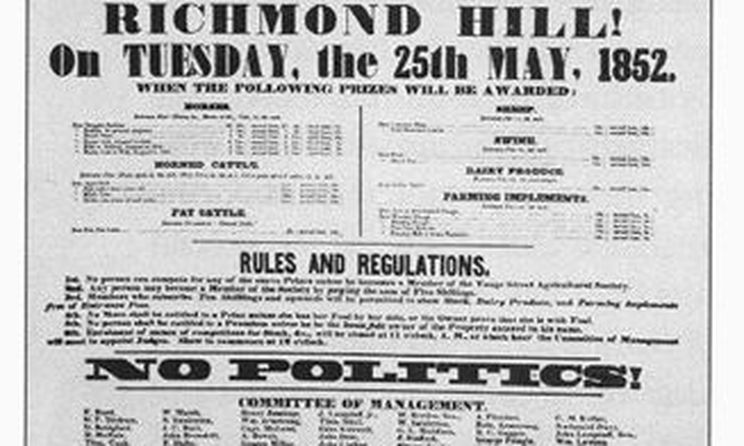

By April of that year, several letters were received by the Liberal from readers distraught about the length of time it was taking to build the new high school. The Liberal’s editor realized that there was enough interest for a regular column from readers who could vent their frustrations to the public. Some wrote in with full lists of disapproving facts. One petition that had been circulated throughout the village claimed that the board had made a mistake in its selection of the Hopkins property site. The board decided to take its plans to the Ministry of Education, where the petition was disallowed. Those named in the petition who had favoured the Yonge Street site saw the old grammar school of 1851 get torn down, which was donated by Abraham Law, who became the first reeve of Richmond Hill.

The board had already approved the first site, had received the $3,000 needed to build the school and had asked for the $1,500 for costs associated with the planning and design of the building from John Harris.

In May, it was again suggested that the Hopkins property be purchased at Yonge and Wright Streets. The board, which met weekly, had also considered six other locations, but it was Mr. McConaghy who pointed out to the board that Chapter 57 of Section 46 of the High School Act precluded Mr. McNair from selling the Hopkins property to the board, since he was also the executor. He was also not allowed to vote. It was moved that the chair and secretary act as a committee and buy the Hopkins one-and-a-quarter-acre lot for $1,000.

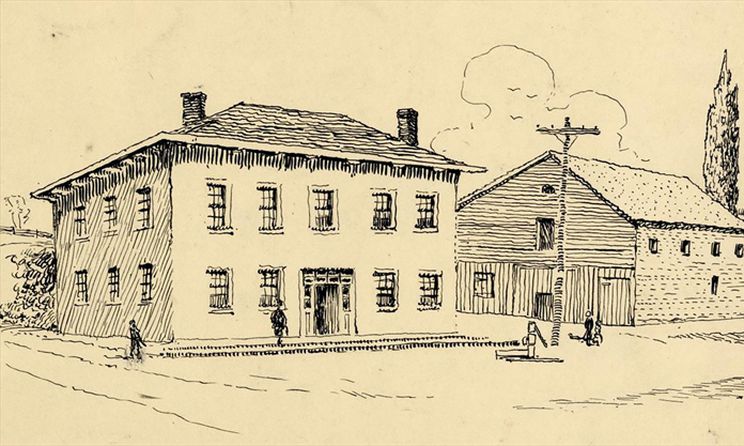

Construction of the brand-new high school officially began at the corner of Yonge and Wright streets in June 1897, just a few weeks before village residents celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Masonry work was completed by J. Kelly and the lumber work by L. Innes and Sons. J. Francis Brown, who was a leading and remarkably prolific architect in the industry at the time, was the architect for the project.

The new school was officially opened on December 30, 1897, just one year from the time the former one had been burned down. There was a great pride of accomplishment felt in the community when the new high school was finally completed. It was referred to as a “monument” to both its builders and architects. Its exterior laid out in red brick with grey stone foundation accommodated two entrances, as well as a rear entrance to the basement sitting neatly on the Mill Street lot.

With well-lit classrooms and a science room “supplied with every apparatus for practical work,” the entire building was heated in the winter and ventilated in the summer, and was perfectly modern for its time.

Today, the building still stands proudly at the corner of Yonge and Wright Streets, and it’s worth remembering its history because it recognizes the hard work and effort of the many people involved with this project.

Read the full account of the official opening of the school on the front page of the January 6, 1898, issue of the Liberal, available in the Richmond Hill Public Library’s historic local newspaper archive.