A brief history of the Richmond Hill Cenotaph by Peter Wilson

Originally published online by the Richmond Hill Liberal on April 14, 2020

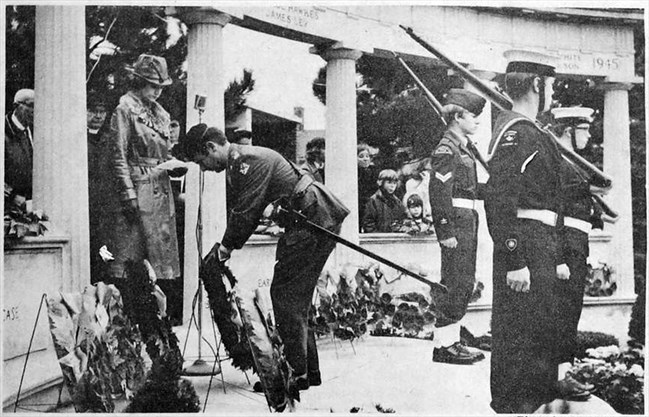

For nearly a century, the Richmond Hill Cenotaph has stood sentinel in the heart of the city. At the time of its 1923 unveiling, Col. William Nisbet Ponton declared: “Their names are engraved forevermore in the stone of remembrance.” He added that, “the situation of the monument, in the centre of the loyal county of York, before a schoolhouse, where it would inspire the generations of future citizens was also most appropriate.”

The Cenotaph’s origins date to a village council meeting of Feb. 13, 1918, where Reeve William Pugsley suggested something to honour the memory of “our boys who have fallen in the war.” The reeve and village clerk A.J. Hume were directed to research a suitable memorial, and within a month proposals were received from several marble dealers. At the council’s Dec. 16, 1918 meeting, a motion passed to commission a monument similar to a model by the Thomson Monument Company.

Reeve Thomas H. Trench organized a meeting for June 9, 1919 at the Masonic Hall to launch a fundraising campaign. In addition to a subscription scheme, a resolution was passed asking ratepayers to co-operate with council’s holding a Field Day on Aug. 4, 1919; the first of many with proceeds earmarked for the building of a monument.

Fundraising and planning took another four years, in which the future of the Cenotaph was put to question. At the Field Day meeting June 26, 1922, considerable interest was voiced over having a Memorial Hall instead. But the majority of returning soldiers preferred a monument, a point well-articulated in a heartfelt November 1922 letter by Louis Teetzel to The Liberal. He wrote, “(the soldiers) have won a place in the world’s history for all time to come … we express ourselves in favour of a permanent monument … that will keep alive in the people the sentimental side of the memorial.”

To settle the matter, a referendum was held during the municipal election on Jan. 1, 1923. It was resoundingly in favour of a monument: 170 votes to 55.

Finally, the Cenotaph was designed by Toronto architect Charles MacKay Willmott — and built at a cost of $4,960 by Nicholson and Curtis (stonework), J. Reynolds (lettering), J. Sheardown (foundation), J. T. Startup (levelling and sodding), and the Architectural Bronze Co. (lamps).

It was dedicated on Aug. 5, 1923, during the Grand Reunion of the Old Boys and Girls. It originally honoured the six individuals etched on the bottom panels who lost their lives in the Great War. A seventh, Starr McMahon who died in 1918 with the Merchant Navy, was added later. And the five-sided stone recognizes 36 soldiers from the First World War, “who so nobly served and by the grace of God whose lives were spared.”

Sadly, the Second World War required the addition of 13 names along the top of the monument. Later plaques recognized those who died in the cause of peace in Hong Kong during the Second World War, as well as those who died in the Korean War and on deployment as peacekeepers.

We will remember.

—Peter Wilson is a member of the Richmond Hill Historical Society. He is also the Local History and Genealogy Librarian at Richmond Hill Public Library.

Names of the Fallen

The following heroes from our community made the ultimate sacrifice during the First World War and the Second World War. These are the brave men whose names are etched on the Richmond Hill Cenotaph.

The First World War

C. Cleland Caldwell

William Case

Arthur C. Cooper

Earl Hughes

Starr McMahon

Wellington C. Monkman

Harold Rowley

The Second World War

Jack Beresford

Fred Carter

Jack Collin

Ernest Goode

Donald Graham

Fred Greene

George Hawkes

James Ley

Vernon Mitchell

Roy Russell

John Sloan

Ernest White

Eric Wilson