by Peter Wilson

The first Women’s Institute (WI) was formed in Stoney Creek, Ontario on February 19, 1897 by Erland and Janet Lee, who invited approximately 100 women to hear educational reformer Adelaide Hoodless. Ms. Hoodless turned the personal tragedy of the death of her 14 month old son into a movement that encouraged women to see the importance of domestic science education and to be advocates in areas of health, education and community service. Since its inception, there have been upwards of 1,500 branches of the WI across the province of Ontario. While most have disbanded over the years, the Institute continues with 220 active branches across the province. Their motto “For Home and Country” was adopted by the Institute around 1904.

RICHMOND HILL WOMEN’S INSTITUTE

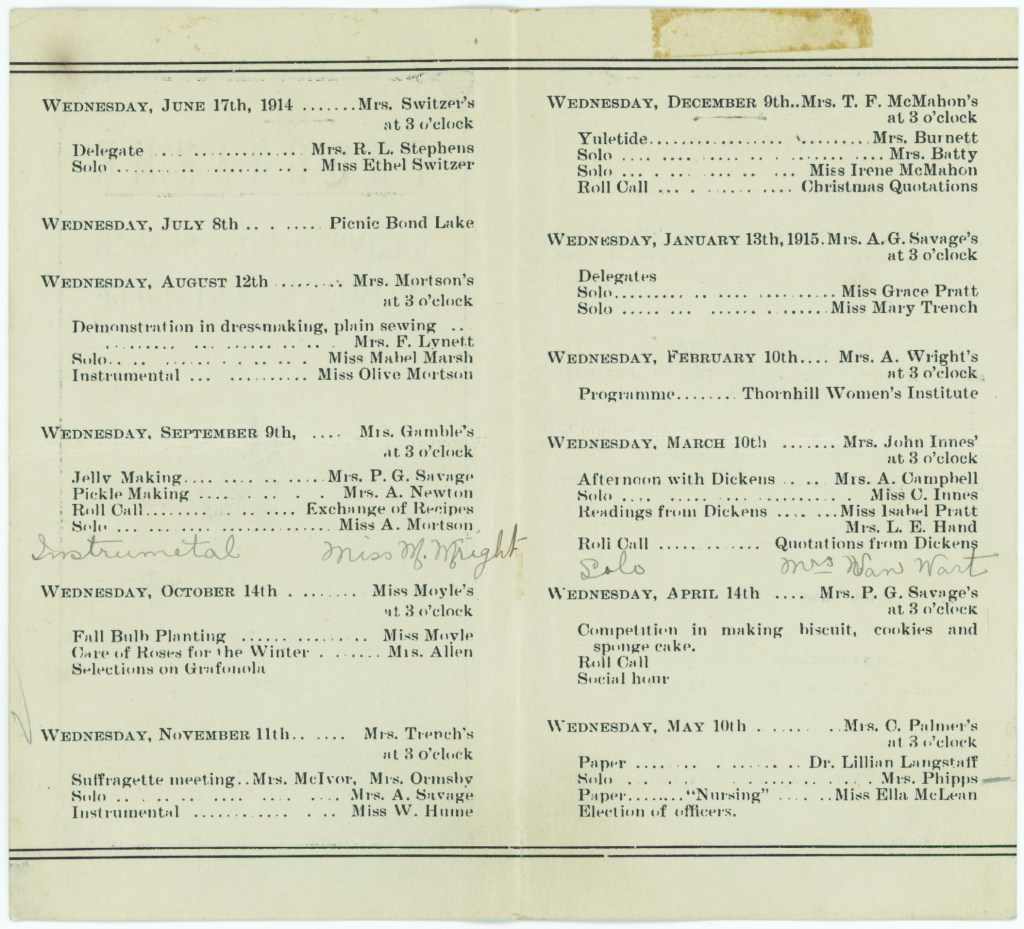

The Richmond Hill branch of the Women’s Institute (RHWI) was formed in 1913 and held its organizational meeting on January 27th at the Masonic Hall on Yonge Street. The first keynote presentation was delivered by Dr. Lillian Langstaff, who spoke on the topic of “Facts about Flies,” beginning a long history of talks on home economics and health. Presentations and demonstrations included sewing and dressmaking, baking, canning and preserving, flower arranging and more. Monthly meetings presented opportunities to socialize, learn and develop skills, pursue personal interests, but perhaps most importantly, to plan and carry out work to the benefit of the entire community.

The lasting impact of the RHWI was in their educational, charitable and civic-minded pursuits. Some key highlights included: the introduction of medical inspections in schools resulting in the appointment of school nurses; actively working towards obtaining the rights of women to vote; advocating for playgrounds for children; the introduction of litter receptacles on Richmond Hill streets and the beautification of village in cooperation with the Richmond Hill Garden and Horticultural Society; and the donation of pianos and other furnishings to our elementary and secondary schools. The Institute also undertook years of advocating and fundraising for a new public library building, which culminated in a donation in 1949 of over $1,700 dollars. That library would eventually be built on Wright Street in 1959.

The Women’s Institute also undertook war and relief work, which began in 1914 with the purchase of cloth to be rolled into bandages for a women’s hospital ship. In that same year, food was gathered for soldier’s families in need. Collections were undertaken for Belgian and Armenian relief. Members helped support the Red Cross as well as providing donations for war relief. During the Depression, they undertook relief work, in cooperation with teachers, for the unemployed.

Representatives of the Richmond Hill WI were appointed to a number of boards across the community, where they were able to add an important voice to decisions being made for the benefit of all. Their focus on women’s issues and education positioned them well for having a profound and valuable impact to the lives of residents. Their spirit and drive helped them support many in need, not just in our community, but around the world. Their accomplishments and impact on people’s lives is impossible to fully articulate here.

TWEEDSMUIR HISTORY OF RICHMOND HILL

One of the most valuable and enduring legacies of the RHWI is the Tweedsmuir History of Richmond Hill. The Richmond Hill Public Library holds the original and digitized copies. The Tweedsmuir History Books, chronicles of local history, were created all across Ontario in the name of John Buchan, The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir, Governor General of Canada from 1935-1940.

The Tweedsmuir History of Richmond Hill was begun in April 1949 and transferred into its final form in 1957. The work was coordinated by their Tweedsmuir History Committee and is in the form of a scrapbook with a mix of typed and scrapbook pages. It contains a number of photographs, newspaper clippings, postcards, letters, family histories, and other ephemera covering a wide variety of current events of the day, local individuals and families, and historically significant local events.

They say that all good things must come to an end and this is what transpired for the RHWI, officially disbanding in 1964. For a write up of the end of the Institute, see “Richmond Hill Women’s Institute,” in The Liberal, June 25, 1964, p. 2 (https://history.rhpl.ca/3216109/page/3). For home and country and for everything (and everyone) in between; our lives and communities have been made better from their enduring legacy.

Peter Wilson is a librarian at the Richmond Hill Public Library and editor of the Richmond Hill Historical Society’s newsletter and website.

Richmond Hill Tweedsmuir History Highlights

The Richmond Hill Tweedsmuir History can be viewed in the Richmond Hill Public Library’s Digital Archive.

• a history and records of achievement of the Institute

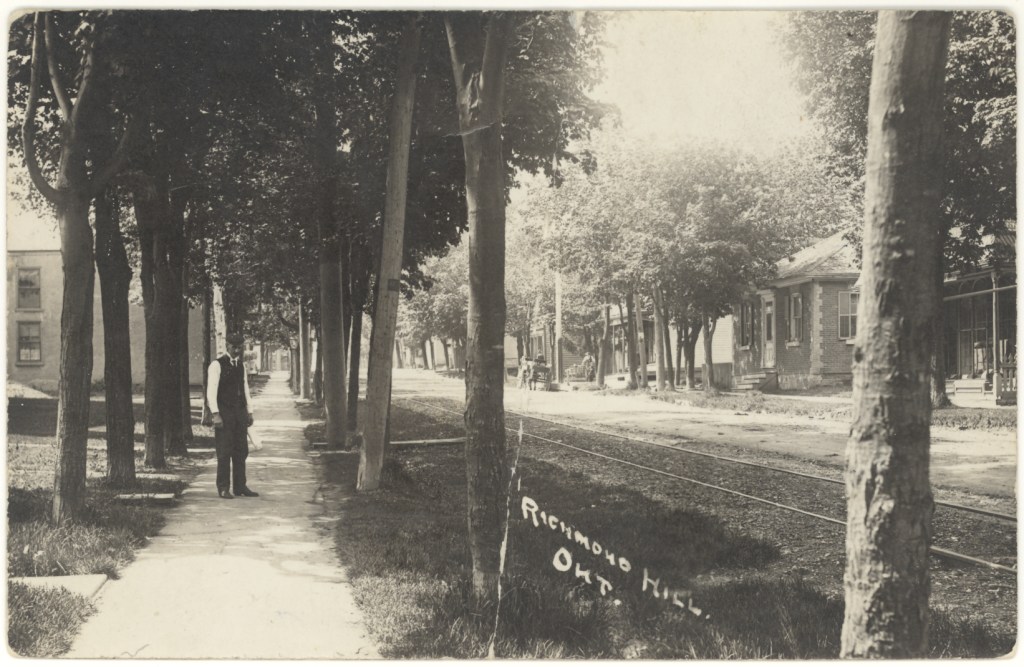

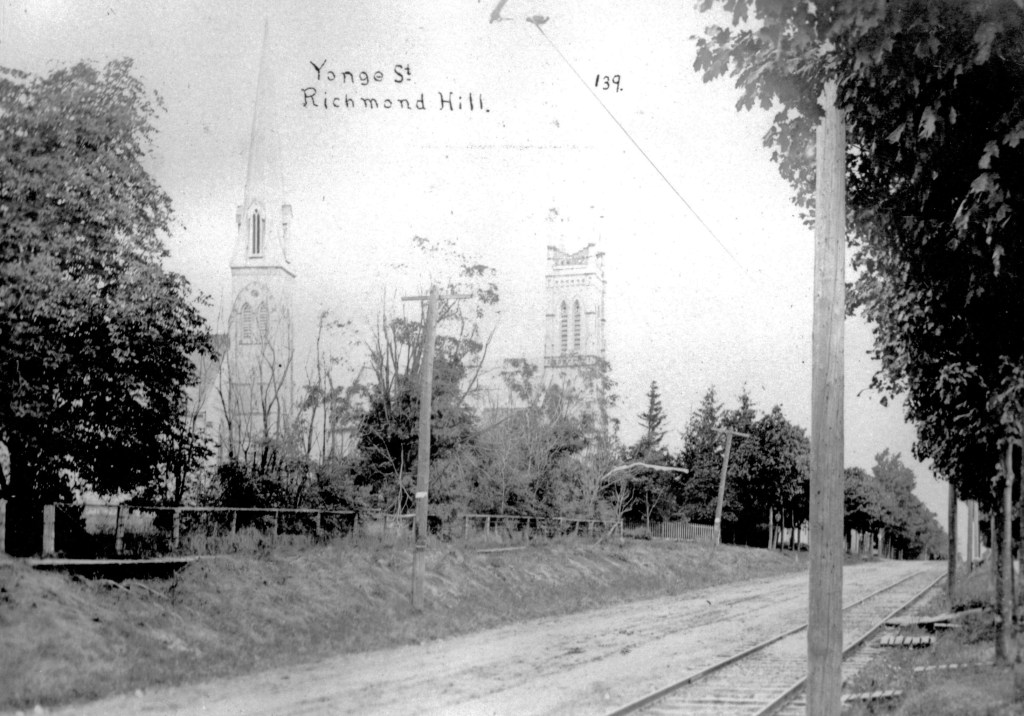

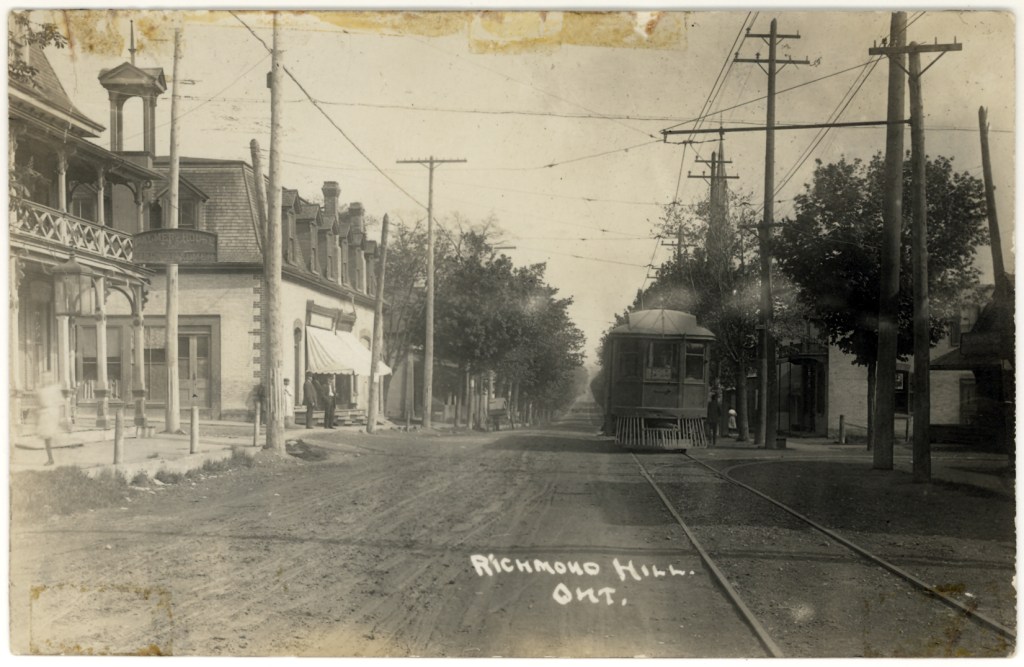

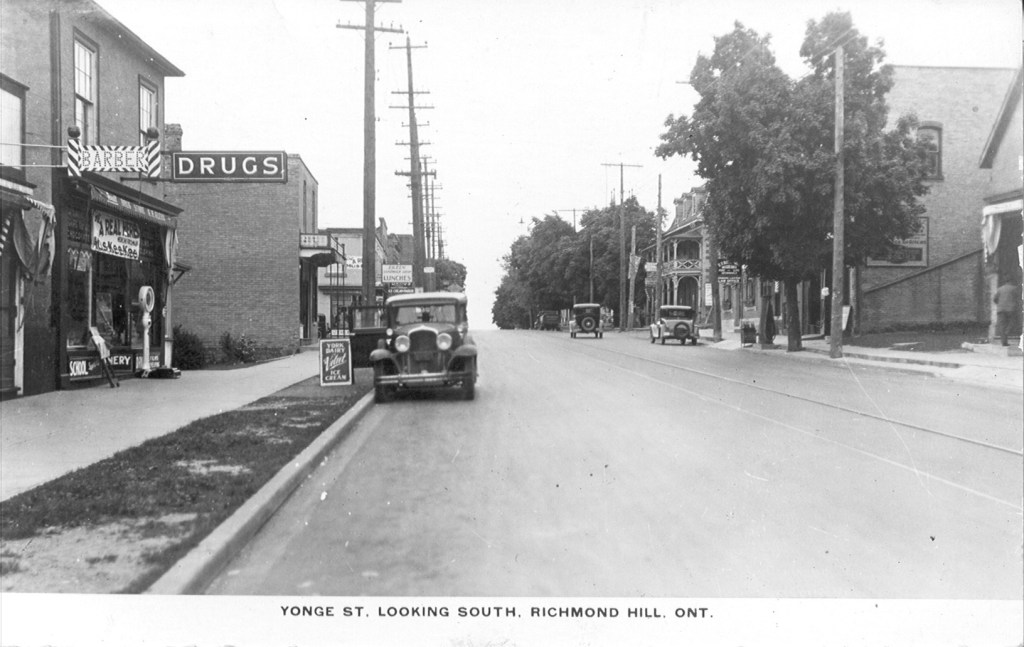

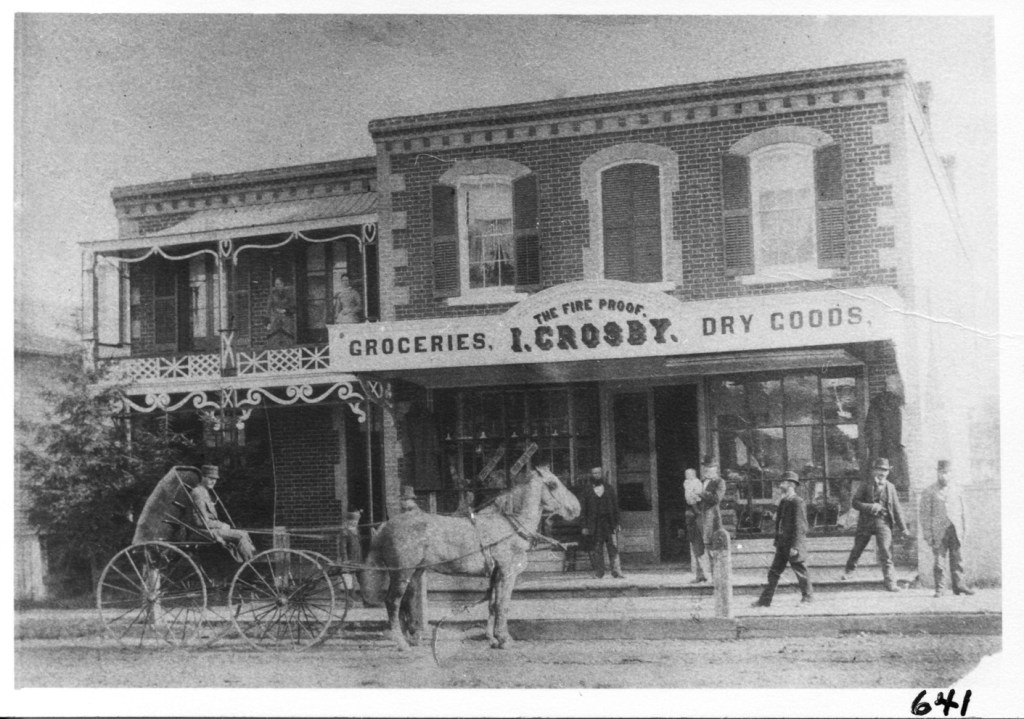

• recounting the early days in Richmond Hill

• biographies of early settlers: Abner Miles, Hugh Shaw, Col. Wilmot, John Stooks, Col. David Bridgford, James Miles, John Stegman, the de Puisaye settlers, Quetton St. George, Col. Robert Moodie, the Playters and the Langstaff family

• a history of Yonge Street

• a history of early mills in Richmond Hill

• biographical sketches of notable past residents: Amos Wright, William Wright, William Powell, Susannah Maxwell, Matthew Teefy, Alex Hume, Thomas McMahon, Nicholas Miller, William Trench, Francis Boyd, the Wilkie family, Robert Marsh, John Switzer, David Boyle, Samuel Thompson, John Coulter, Leslie Innes and Robert Hopper

• listing of the village residents of 1871

• listing of Reeves and Councillors

• school and church histories

• history of the mechanics’ institute and library

• unique historical documents related to Thomas Kinnear, murdered with Nancy Montgomery in 1843

• residents who served in First and Second World Wars

• histories of the Atkinson and Trench families

• reminiscences of Dr. Rolph Langstaff (1950s)

• extensive coverage of current events of the 1950s